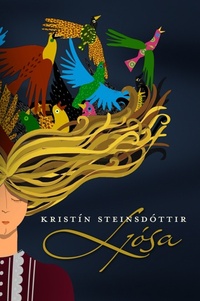

Kristín Steinsdóttir

“I was reaching for things that were simply gone,” says author Kristín Steinsdóttir of her latest novel, Ljósa, which is based on the life of her grandmother. Mental illness, Kristín tells us, was not something people used to discuss. “Perhaps people felt that, just by talking of it, they put themselves at risk of falling ill.”

Kristín Steinsdóttir's novel Ljósa was one of last year's hits, with critics and readers alike. Broaching the thorny subject of mental illness in rural turn-of-the-century Iceland, the book was immediately well received, and since we last spoke to Kristín late in 2010, the work has gone on to collect the Icelandic Women's Literature Prize and the DV Cultural Prize. Kristín still has her hands full these days: the book – still on the country's bestseller lists – is popular with reading rings, which Kristín visits whenever she can, to read from the book and discuss it. In other news, the German audiobook Leben im Fisch (Living With Fish), in which Kristín relates her childhood in Eastern Iceland., was published by Supposé early in 2011, and was recently featured as Audiobook of the Month on the Radio Station HR2. The translation rights Ljósa were also recently bought by the German publishing house C. H. Beck.

In Ljósa, the reader is introduced to the titular character, an exuberant, well-born and artistically gifted young woman, who nevertheless loses control of her life as she descends into mental illness. The inspiration for the story came from the life of Kristín's grandmother, who suffered from bipolar disorder. A great deal of work went into gathering material for the novel, and Kristín first got started on the project almost two decades ago.

In Ljósa, the reader is introduced to the titular character, an exuberant, well-born and artistically gifted young woman, who nevertheless loses control of her life as she descends into mental illness. The inspiration for the story came from the life of Kristín's grandmother, who suffered from bipolar disorder. A great deal of work went into gathering material for the novel, and Kristín first got started on the project almost two decades ago.

“I wanted the result to be plausible without being just a collection of facts,” she says when asked about the required research. “I had to prevent various modern details from creeping into the story, and that meant a great deal of work. For instance, 19th century farming was an alien phenomenon to me, but everything had to add up so that the credibility could be maintained. Aside from farming, the biggest factor was definitely the mental illness itself. Portraying it faithfully was an absolute priority when I wrote the book – relating how the character feels during an upswing, how she feels when she starts to come down again.

“Grandmother died more than fifty years before I began thinking of the work, and although my family and the people in the district who remembered her answered my questions as best they could, it was plain to see that the illness hadn't been discussed much. Talking about these matters just wasn't appropriate. Perhaps people felt that, just by talking of it, they might set something in motion and put themselves at risk of falling ill.”

An instrument of despair

How did people deal with bipolar disorder back then?

“Of course, a doctor would arrive if one was available, and he would be able to help, up to a point, by administering tranquilizers and sedatives to keep the patient calm. Some doctors would talk to the patients; it was conversational therapy similar to what we know today. I know this was a help to my grandmother. However, there wasn't much of this out in the remote districts, because the next doctor was a long way off. People would say that it was more important to get hold of a good carpenter, because he could make a so-calleddárakista, or “fool's cage,” for the sick person. I describe this in the book. The carpenter was thought more important than the doctor, it's a horrible thought.

“Although I began work on the book around 1990, I regret not getting started even sooner. By the time I started, I had lost people who could have told me more, for example about the fool's cage, and even drawn it for me. Naively, I thought I could just go and find one somewhere. But when I went looking, there wasn't much documentation on the subject. I went to the Árbær Museum, expecting to find a fool's cage, but it has completely and utterly vanished. There was nothing at the Medical Museum in Seltjarnarnes either. People just looked at me quizzically. “Fool's cage?” I was asking for things that had simply vanished.”

Things people would rather forget, perhaps?

“Yes, this was something people preferred to forget, and perhaps that's understandable. These cages were cobbled together back here in Iceland, and they were a desperate measure. The fool's cage was an instrument of despair. When I started writing the book I grew so angry. I felt my grandmother had been treated so badly, she had been locked up. But, looking better into the matter, I saw that life must continue. You couldn't have someone looking after the sick person around the clock, when there was farming to be done, mowing, haymaking and god knows what else. In some cases it may have been done out of malevolence, and perhaps people were locked up too soon, but I can't pass judgement on that. As we know, people lived in very close quarters in those times, which no doubt intensified the problem. I think it would be healthy for everybody to imagine how they would have reacted to living with a person who was this sick, who made no distinction between day and night, cried out, sang, shouted and ranted – all night long, for that matter.”

“Don't let anyone push you around!”

Ljósa is you third book to be written with adult readers in mind. You have, however, long been one of Iceland's most popular author's of children's books. It is often remarked that the children's book Engill í Vesturbænum (An Angel On The 2nd Floor)was a pivotal work in your career. Did that book change you as an author?

“Looking back, it's plain to see that An Angel on the 2nd Floor was a forerunner of the grown-up books. I was in a whole different zone by the time I wrote it. Two years before it was published, I moved to Reykjavík. It had nothing to do with how I felt while was in Akranes – I just needed a change. Moving into West Reykjavík seemed to make me so free, I always had the feeling I was floating, not walking. I rented an apartment on the fourth floor above Melabúðin, the local grocery store. Looking through my window, I could see Hallgrímskirkja Church on one side, The Catholic Church on the other, and my kitchen window had a view of Snæfellsjökull Glacier – which I knew like the back of my hand after living in Akranes. I felt like Odin sitting on his throne Hliðskjálf, like I could see the entire world, even if I was only living on the fourth floor! I felt so liberated, and then Angel on the 2nd Floor came into being.”

That book introduced the deeper layer of meaning that lead you to writing for adults?

“I gave myself permission to do something completely different, to dare stand by it. Angel on the 2nd Floor is no less for adults than children. For the longest time, I had been aware of a need for delving deeper. With that book, I feel I closed one door and moved to a different level.

“The first work I wrote for adults, Sólin sest að morgni (The Sun Goes Down at Dawn, 2004) had also been with me for a long time before it was published. This was two years after An Angel on 2nd Floor. I had written the story many times in my head, really. To begin with, writing for children had been all I could see. Then, I began to want to write for adults. But when I took the manuscript to my publishing house, they couldn't see the point of all this fussing around. I had won all these awards for writing children's books. Shouldn't I just stick to that?

“When the book was finally published, I was trembling with apprehension over having a work for adults out. And at that point I had published almost thirty children's books! But here I found myself in a new place, a new environment, and the book got very good reviews. So, nerve-wracking as it was, it's still very enjoyable in retrospect!”

So mobility between different fields of literature is healthy?

“Yes, very healthy. Today I wouldn't let anyone tell me to stay put, to behave. Of course there are many people who move between literary fields, and surely I'm all the richer for not staying in one place for my entire life. It's easy to become isolated that way. You think differently when writing for adults, and the next time you write for children you make a fresh entrance. Don't let anyone push you around!”

Interview: Davíð K. Gestsson

Translation: Steingrímur K. Teague