From Sagas to Novels

Just as medieval poets and scholars traveled from Iceland to the mainland and made pilgrimages to Rome or sailed to Trondheim or Paris to study, Icelandic contemporary authors have made the world their subject.

Where to begin when describing Icelandic literature? Should the story start in the year 1000 when, according to the Icelandic scholar Sigurður Nordal, the Völuspá – one of the most beautiful and dramatic poems in Old Norse literature – was composed in Iceland? Whatever the case may be, it is certainly not possible to ignore medieval Icelandic literature, which has not only played a major role in the history of the nation but is also Iceland's chief contribution to world culture.

Where to begin when describing Icelandic literature? Should the story start in the year 1000 when, according to the Icelandic scholar Sigurður Nordal, the Völuspá – one of the most beautiful and dramatic poems in Old Norse literature – was composed in Iceland?

Where to begin when describing Icelandic literature? Should the story start in the year 1000 when, according to the Icelandic scholar Sigurður Nordal, the Völuspá – one of the most beautiful and dramatic poems in Old Norse literature – was composed in Iceland?

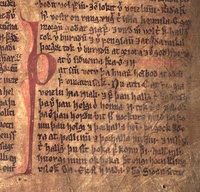

Whatever the case may be, it is certainly not possible to ignore medieval Icelandic literature, which has not only played a major role in the history of the nation but is also Iceland's chief contribution to world culture.Saga Noregskonunga (The History of the Kings of Norway) was written in Iceland.

The Icelandic sagas were written in the 13th and 14th centuries and are unique for many different reasons. They are not structured like chronicles or local legends; instead they are stylistically more akin to modern novels and their stories are told with great artistry. No one knows who wrote these books. The sagas tell of the settlement of Iceland and the division of the land between families, the establishment of law and the structuring of society, and conflicts based on personal interests or honor. These conflicts often developed into complicated patterns of violence and retribution, culminating historically in a full-blown civil war in the 13th century, which led to Iceland's coming under the control of Norway and later Denmark. Iceland was a Danish colony for more than six centuries, but during that entire time Icelanders continued to copy, read, and discuss the old sagas.

"It is certainly not possible to ignore medieval Icelandic literature, which is Iceland's chief contribution to world culture."

During Iceland's struggle for independence in the 19th century, its politicians realized the possibilities of using the country's medieval literature for political purposes. In order to prove that the colony had cultural value of which it could be proud, these politicians and others pointed to the Icelandic sagas to show that during Iceland's early days of independence its men had been valiant heroes and its women beautiful and proud, and that the sun had shone continually on this exemplary state. Little by little the ties between Iceland and Denmark loosened; Iceland attained sovereignty in 1918 and finally complete independence in 1944.

During Iceland's struggle for independence in the 19th century, its politicians realized the possibilities of using the country's medieval literature for political purposes. In order to prove that the colony had cultural value of which it could be proud, these politicians and others pointed to the Icelandic sagas to show that during Iceland's early days of independence its men had been valiant heroes and its women beautiful and proud, and that the sun had shone continually on this exemplary state. Little by little the ties between Iceland and Denmark loosened; Iceland attained sovereignty in 1918 and finally complete independence in 1944.

Shortly after Iceland's sovereignty was recognized, Þórbergur Þórðarson (1888 – 1974) published a novel that was as far removed from an Icelandic saga as could possibly be. It was characterized by a new “subjectivity”; modernity had come to stay. Þórbergur Þórðarson's novel was Bréf til Láru (Letter to Lára, 1924), a hybrid text that combined letters, essays, short stories, fantasy, and humor. In place of the objective style of the Icelandic sagas, this novel displayed a subjective, unruly self-expression that put Icelandic readers ill at ease.

"During Iceland's struggle for independence in the 19th century, its politicians realized the possibilities of using the country's medieval literature for political purposes."

Around the same time, another very young Icelandic writer, Halldór Laxness (1902 – 1998), wrote a letter to a friend of his in which he declared that he knew of no type of writing more boring or obsolete as the works of Snorri Sturluson and other medieval writers; the Icelandic sagas were primitive concoctions of no relevance to the modern world. Laxness believed he had urgent business with his contemporaries, as can be seen in his novel Vefarinn mikli frá Kasmír (The Great Weaver from Kashmir, 1927), which describes a young man's passionate search for himself, a search that takes him across Europe and ends with him rejecting the confused and crazy world, becoming a Catholic and entering a monastery. Halldór Laxness wrote the book for the most part in Taormina in Sicily. The Great Weaver from Kashmir was supposed to be Laxness's ode to the Catholic Church, but with this book he in fact wrote himself off from the Church. The next that Icelanders heard from him was after he had travelled to Los Angeles and become a communist; now he busied himself with preaching to his countrymen about materialism and scientific socialism. Þórbergur Þórðarson and Halldór Laxness dominated the landscape of Icelandic literature for a major part of the 20th century, and both had strong opinions as to what Icelandic culture was or should be.

Around the same time, another very young Icelandic writer, Halldór Laxness (1902 – 1998), wrote a letter to a friend of his in which he declared that he knew of no type of writing more boring or obsolete as the works of Snorri Sturluson and other medieval writers; the Icelandic sagas were primitive concoctions of no relevance to the modern world. Laxness believed he had urgent business with his contemporaries, as can be seen in his novel Vefarinn mikli frá Kasmír (The Great Weaver from Kashmir, 1927), which describes a young man's passionate search for himself, a search that takes him across Europe and ends with him rejecting the confused and crazy world, becoming a Catholic and entering a monastery. Halldór Laxness wrote the book for the most part in Taormina in Sicily. The Great Weaver from Kashmir was supposed to be Laxness's ode to the Catholic Church, but with this book he in fact wrote himself off from the Church. The next that Icelanders heard from him was after he had travelled to Los Angeles and become a communist; now he busied himself with preaching to his countrymen about materialism and scientific socialism. Þórbergur Þórðarson and Halldór Laxness dominated the landscape of Icelandic literature for a major part of the 20th century, and both had strong opinions as to what Icelandic culture was or should be.

During the Depression and WWII Halldór Laxness produced one great literary work after another; he wrote about Salka Valka, a female fish worker in a seaside village; the farmer Bjartur of Summerhouses, a farm on an isolated heath; the popular poet Ólafur Kárason and the female laborer Ugla, who travels from the north to Reykjavik and witnesses the chaos and cultural inequalities of the city in the wake of the war. By this time Laxness had completely changed his views on his country's medieval literature. Iceland's literary heritage had been used to strengthen national pride during the country's struggle for independence and thus became closely connected with Icelanders' newly-developed patriotic con-sciousness; the Icelandic sagas represented the origin of this heritage and were accorded the status of sacred texts. Laxness and his friends were very interested in reclaiming medieval Icelandic literature from the clutches of the nationalists and published several of the sagas with modern spelling for the general public, underlining the fact that the sagas were a living literature.

"In 1955 Laxness received the Nobel for infusing medieval Icelandic literature with new life and new roles through interpretations and innovations."

This worked in an interesting way, since the existential sympathies of the Icelandic sagas and their objective, concise narrative method fell in well with literary trends of the post-war years; the sagas' style was not dissimilar to that of Hemingway, among other modern authors. In 1952 Halldór Laxness then published his own Icelandic saga, the novel Gerpla (The Happy Warriors, 1952), which tells of two friends, the hero and the poet, who dream of becoming soldiers and courtiers to St. Ólafur, the king of Norway (995 – 1030). One of the two friends becomes a mercenary in England and finds himself face-to-face with the horrors of murder and the plundering of the Vikings; the other sacrifices everything he holds dear to deliver his poem to the king and express his fealty to him. By the time the poet finally meets his king he has become richer for the experience and neither the leader nor the praise poem matter any longer. The novel is in part a reckoning with and criticism of the dictators Hitler and Stalin and the soldiers and poets who followed them blindly. It is also Laxness's reckoning with those who wished to put the saga tradition into the service of a romantic interpretation of the past and nationalism. In 1955 Laxness received the Nobel Prize for infusing medieval Icelandic literature with new life and new roles through his interpretations and innovations. Halldór Guðmundsson has written a dramatic biography of Halldór Laxness, for which he received the Icelandic Literary Prize in 2005.

Gerður Kristný (1970-) gave readers another dramatic, feminist reckoning with the violent rhetoric of the Icelandic literary heritage in her poetic work Blóðhófnir (Bloodhoof, 2010), which was awarded the Icelandic Literary Prize in 2010. In an intense, powerful narrative poem, Gerður reveals the way in which the myth of how the fertility god Freyr steals his bride from her exotic tribe, the giants, is based on violence, coercion and suffering, as seen from the perspective of the maiden.

Gerður Kristný (1970-) gave readers another dramatic, feminist reckoning with the violent rhetoric of the Icelandic literary heritage in her poetic work Blóðhófnir (Bloodhoof, 2010), which was awarded the Icelandic Literary Prize in 2010. In an intense, powerful narrative poem, Gerður reveals the way in which the myth of how the fertility god Freyr steals his bride from her exotic tribe, the giants, is based on violence, coercion and suffering, as seen from the perspective of the maiden.

In 1940 the British occupied Iceland due to the great strategic importance of its location, and in 1941 the Americans took over. The occupation had a huge financial, social, and cultural impact on the country. Signs of this can be seen clearly in the literature of the post-war years, which often expresses either nostalgia for the old farming society or a modernist consciousness of loss, separation, and both personal and social depression. Modernism appeared as an artistic movement in Iceland in the 1960's, first in painting, then in poetry and finally in prose literature, and the gap between high and low culture widened.

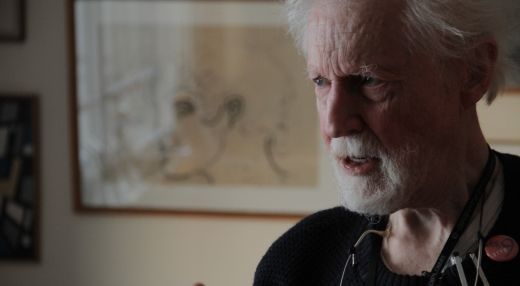

The writers who upheld modernism in prose were Svava Jakobsdóttir (1930 – 2004), Thor Vilhjálmsson (1925 – 2011), and Guðbergur Bergsson (1932 –).

Svava Jakobsdóttir was a leading figure in the second wave of feminism in Iceland, a journalist, member of parliament, and an author. She was a prolific producer of short stories, plays, and novels, utilizing both irony and grotesque humor in innovative ways. Guðbergur Bergsson followed close on her heels and achieved success with his novel Tómas Jónsson metsölubók (Tómas Jónsson Bestseller, 1966) which shocked Icelandic readers in innumerable ways, lashing out as it does at Icelandic society of the post-war years for its cultural confusion, amorality, and hypocrisy. The main character is a grumpy old man who speaks and writes in various styles, grumbles and babbles and criticizes everything that appears in his own imaginative world. Guðbergur's (post)modernist task was to identify the social instabilities in the life of the newly independent post-colonial nation that did not know what it was. Thor Vilhjálmsson was one of the modernists who changed the Icelandic cultural life in 1960's, and in his book Fljótt fljótt sagði fuglinn (Quick Quick, Said the Bird, 1968) he reveals a new and splintered worldview that nevertheless has its foundation in the old myths, folktales, and ancient saga motifs. Thor's novels were cosmopolitan, restless, and often under the influence of new films, while in the 1980's his focus turned to Iceland, the setting for the dramatic novel Grámosinn glóir (Justice Undone, 1986), which earned Thor the Nordic Council Literature Prize (1988).

Guðbergur Bergsson followed close on her heels and achieved success with his novel Tómas Jónsson metsölubók (Tómas Jónsson Bestseller, 1966) which shocked Icelandic readers in innumerable ways, lashing out as it does at Icelandic society of the post-war years for its cultural confusion, amorality, and hypocrisy. The main character is a grumpy old man who speaks and writes in various styles, grumbles and babbles and criticizes everything that appears in his own imaginative world. Guðbergur's (post)modernist task was to identify the social instabilities in the life of the newly independent post-colonial nation that did not know what it was. Thor Vilhjálmsson was one of the modernists who changed the Icelandic cultural life in 1960's, and in his book Fljótt fljótt sagði fuglinn (Quick Quick, Said the Bird, 1968) he reveals a new and splintered worldview that nevertheless has its foundation in the old myths, folktales, and ancient saga motifs. Thor's novels were cosmopolitan, restless, and often under the influence of new films, while in the 1980's his focus turned to Iceland, the setting for the dramatic novel Grámosinn glóir (Justice Undone, 1986), which earned Thor the Nordic Council Literature Prize (1988).

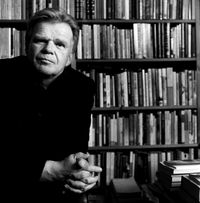

Einar Kárason (1955 –) has also turned to medieval Icelandic literature and paid homage to the saga heritage in his own way, after having won the hearts and minds of readers with his trilogy on the Quonset-hut neighborhoods of Reykjavik in the 1960's. He has also tapped into Sturlunga saga with the intention of bringing the past into the future. In the novels Óvinafagnaður (Gathering of Foes, 2001) and Ofsi (Fury, 2008) he focuses on the conflicts between Icelandic chieftains in the 13th century. The roots of these conflicts lie in the ”honor” of the leading figures and in the name of this ”honor”, envy, rivalry, and hatred grow and come to a climax in revolting mass murder.

Einar Kárason (1955 –) has also turned to medieval Icelandic literature and paid homage to the saga heritage in his own way, after having won the hearts and minds of readers with his trilogy on the Quonset-hut neighborhoods of Reykjavik in the 1960's. He has also tapped into Sturlunga saga with the intention of bringing the past into the future. In the novels Óvinafagnaður (Gathering of Foes, 2001) and Ofsi (Fury, 2008) he focuses on the conflicts between Icelandic chieftains in the 13th century. The roots of these conflicts lie in the ”honor” of the leading figures and in the name of this ”honor”, envy, rivalry, and hatred grow and come to a climax in revolting mass murder.  Einar Már Guðmundsson (1954-) also writes about venomous conflicts, but focuses on the present day in Hvíta bókin (The White Book, 2009), a work on Iceland's financial collapse. Many have compared the modern fiscal situation to the power struggles and greed of the Sturlung Age. Einar Már Guðmundsson won the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 1995 for Englar alheimsins (Angels of the Universe, 1993), a powerful, tragicomic novel about a young, schizophrenic artist. The film director Friðrik Þór Friðriksson made a splendid film based on this novel.

Einar Már Guðmundsson (1954-) also writes about venomous conflicts, but focuses on the present day in Hvíta bókin (The White Book, 2009), a work on Iceland's financial collapse. Many have compared the modern fiscal situation to the power struggles and greed of the Sturlung Age. Einar Már Guðmundsson won the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 1995 for Englar alheimsins (Angels of the Universe, 1993), a powerful, tragicomic novel about a young, schizophrenic artist. The film director Friðrik Þór Friðriksson made a splendid film based on this novel.

Icelandic films have flourished over the past twenty years, often deriving their subjects from intriguing contemporary novels. Ágúst Guðmundsson made a film version of the magical realist novel Mávahlátur (The Seagull's Laughter, 1995) by Kristín Marja Baldursdóttir (1949 –), which enchanted Icelandic readers with its narrative artistry, powerful characterization, and attention to women's rights, as did her books about the female artist Karítas (2004 and 2007), which also narrate the history of art in the twentieth century in an intriguing manner.  Kristín Marja manages to combine a strong focus on plot with intense characterization. The same can be said for another storyteller, Vigdís Grímsdóttir (1953 –), who writes both aesthetically and thematically radical novels about sexuality and death. Ever since the seventies, women have played a strong role in Icelandic literature and changed its form.

Kristín Marja manages to combine a strong focus on plot with intense characterization. The same can be said for another storyteller, Vigdís Grímsdóttir (1953 –), who writes both aesthetically and thematically radical novels about sexuality and death. Ever since the seventies, women have played a strong role in Icelandic literature and changed its form.

Steinunn Sigurðardóttir (1950 –) has written in all of the literary genres, and few Icelandic books have attracted as much attention or touched so many emotionally as her novel Tímaþjófurinn (The Thief of Time, 1986), which tells in a stylistic, humorous way of the ”grand passion” of an upper-class spinster. The book is a philosophical, cutting analysis of the obsessive search for happiness. This is also perhaps the central idea behind a short, unpretentious but brilliant novel by Sjón (1962 –), in which we follow a fox hunter, except that both the hunter and the fox undergo metamorphosis and their struggle in the white snow is by nature unwinnable, by either of them. This novel, Skugga-Baldur (The Blue Fox, 2003), earned its author the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 2005.

Steinunn Sigurðardóttir (1950 –) has written in all of the literary genres, and few Icelandic books have attracted as much attention or touched so many emotionally as her novel Tímaþjófurinn (The Thief of Time, 1986), which tells in a stylistic, humorous way of the ”grand passion” of an upper-class spinster. The book is a philosophical, cutting analysis of the obsessive search for happiness. This is also perhaps the central idea behind a short, unpretentious but brilliant novel by Sjón (1962 –), in which we follow a fox hunter, except that both the hunter and the fox undergo metamorphosis and their struggle in the white snow is by nature unwinnable, by either of them. This novel, Skugga-Baldur (The Blue Fox, 2003), earned its author the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 2005.  Sjón first made his mark as a poet; he was one of the main songwriters for the rock band Sugarcubes and is a colleague and friend of Björk Guðmundsdóttir.

Sjón first made his mark as a poet; he was one of the main songwriters for the rock band Sugarcubes and is a colleague and friend of Björk Guðmundsdóttir.

The same goes for Bragi Ólafsson (1962 –), who was the bass player for the Sugarcubes before leaving music and turning to writing.Bragi Ólafsson's distinctive feature is his subtle, delicate irony that he applies systematically in his novels to shed light on ordinary people in absurd circumstances. Yet another master of the compact form and the unstated is Gyrðir Elíasson (1961 –), who received the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 2011 for his short-story collection Milli trjánna (Between the Trees, 2009).

Gyrðir is both a poet and novelist, known for writing strangely compelling, beautiful and peaceful texts in which there is often an imminent threat, causing the reader to feel that all peace is temporary, that nothing in life comes free and that if the threat does not come from the outside, it comes from within.

Hallgrímur Helgason (1959 –) is both a writer and an artist, but his literary hallmarks are eloquence and rich imagery. His books spin together influences from the media and mass culture combined with world literature, social criticism, and humor. His award-winning novel, Höfundur Íslands (The Author of Iceland, 2001), is about Halldór Laxness. Hallgrímur, like Laxness, has been an active voice in the social dialogue in Iceland, utilizing all means of communication, from books to Facebook.

Hallgrímur Helgason (1959 –) is both a writer and an artist, but his literary hallmarks are eloquence and rich imagery. His books spin together influences from the media and mass culture combined with world literature, social criticism, and humor. His award-winning novel, Höfundur Íslands (The Author of Iceland, 2001), is about Halldór Laxness. Hallgrímur, like Laxness, has been an active voice in the social dialogue in Iceland, utilizing all means of communication, from books to Facebook.

Auður Jónsdóttir (1973 –) is also political, radical, and provocative in her books. She has written a personal account of Halldór Laxness, who was her grandfather. Like so many of the younger writers, Auður is cosmopolitan in outlook and has written about immigrants in Iceland, cultural clashes and ”cultural fault” (dislocation).

She describes the dark sides of globalization in her novel Vetrarsól (Winter Sun, 2008). In Yosoy (2005), Guðrún Eva Mínervudóttir (1976 –) also takes a look at the strange and terrifying aspects of the global consumer society. She tells of an Icelandic ”freak show” in the theater Yosoy, where both external and internal pain is put on display.

Emotional frigidity and loneliness characterize the modern sex industry and both are dealt with by Steinar Bragi (1975 –) in his powerful novel Konur (Women, 2008), which was both praised and debated in Iceland for its cruelty and beauty.

Cruelty is also on the agenda of a complex and compelling work by Eiríkur Örn Norðdahl (1978-): Illska (Evil, 2012), which won the Icelandic Literary Prize the same year.

Cruelty is also on the agenda of a complex and compelling work by Eiríkur Örn Norðdahl (1978-): Illska (Evil, 2012), which won the Icelandic Literary Prize the same year. The novel's narrative is clipped into short scenes, as in a film, allowing it to move rapidly between characters, time periods, and events. The story focuses on three young people in contemporary Reykjavík, and the history of one of them, Agnes, in the village of Jurbarkas in Lithuania, where her ancestors were murdered during the Holocaust. It is ironic that Agnes, the Jew, should fall for the neo-Nazi whom she meets while conducting her research. One of the tasks of this book is to assemble stories of victims and executioners, humanism and dehumanization, first and foremost in order to explore the origins of radical evil.

Cruelty is also on the agenda of a complex and compelling work by Eiríkur Örn Norðdahl (1978-): Illska (Evil, 2012), which won the Icelandic Literary Prize the same year. The novel's narrative is clipped into short scenes, as in a film, allowing it to move rapidly between characters, time periods, and events. The story focuses on three young people in contemporary Reykjavík, and the history of one of them, Agnes, in the village of Jurbarkas in Lithuania, where her ancestors were murdered during the Holocaust. It is ironic that Agnes, the Jew, should fall for the neo-Nazi whom she meets while conducting her research. One of the tasks of this book is to assemble stories of victims and executioners, humanism and dehumanization, first and foremost in order to explore the origins of radical evil.

"In recent years Reykjavik‘s criminal underworld has been mapped by a growing number of writers of crime novels, chief among them Arnaldur Indriðason."

Reykjavik's criminal underworld has been mapped by a growing number of writers of crime novels, chief among them Arnaldur Indriðason (1961 –). Arnaldur was educated as a historian and uses his knowledge and understanding to unveil crimes that often have their roots in the pasts of individuals and families. The same goes for Yrsa Sigurðardóttir (1963 –), who is trained as an engineer and is particularly adept at building up suspense in her novels.

Reykjavik's criminal underworld has been mapped by a growing number of writers of crime novels, chief among them Arnaldur Indriðason (1961 –). Arnaldur was educated as a historian and uses his knowledge and understanding to unveil crimes that often have their roots in the pasts of individuals and families. The same goes for Yrsa Sigurðardóttir (1963 –), who is trained as an engineer and is particularly adept at building up suspense in her novels.

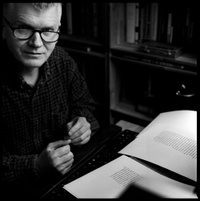

The novels of Jón Kalman Stefánsson (1963 –) look to the vanished rural community with both warmth and humor, and this celebrated stylist manages to combine sincerity and irony in unique ways. In Heaven and Hell (2007), which takes place a hundred years ago, Jón Kalman tells of the struggle of the Icelandic people with the harsh forces of nature, a struggle that is existential in every sense, since it involves giving life meaning through one's actions.

Beauty and basic values are also the subject of the art historian Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir (1958 –) in her unpretentious novel Afleggjarinn (The Greenhouse, 2007), which goes back to a time before consumerism and globalization and starts at the beginning, with the love and thus the trust that arise between a small child and its father.

Beauty and basic values are also the subject of the art historian Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir (1958 –) in her unpretentious novel Afleggjarinn (The Greenhouse, 2007), which goes back to a time before consumerism and globalization and starts at the beginning, with the love and thus the trust that arise between a small child and its father.

"In the same way that the writers of the medieval Icelandic sagas told of the origins of society in Iceland and the voyage from the old homeland to the new, contemporary Icelandic authors bring both history and the literary heritage into the modern world and write novels about sagas."

This trust or “empathy” is perhaps the bud and the origin of all love and Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir's novel contains religious allusions to the rose.

Just as medieval poets and scholars traveled from Iceland to the mainland and made pilgrimages to Rome or sailed to Trondheim or Paris to study, Icelandic contemporary authors have made the world their subject. In the same way that the writers of the medieval Icelandic sagas told of the origins of society in Iceland and the voyage from the old homeland to the new, contemporary Icelandic authors bring both history and the literary heritage into the modern world and write novels about sagas.By Dagný Kristjánsdóttir professor of modern Icelandic literature at the University of Iceland.

Translated by Philip Roughton.