The Codex Regius

The author Andri Snær Magnason ruminates on the density and static energy of art – and poses a question: What is the single most important man-made phenomenon in Iceland?

The author Andri Snær Magnason ruminates on the mass and static energy of art – and poses a question: What is the single most important man-made phenomenon in Iceland?

When considering Iceland's literary and cultural influence, we may begin with a simple question: What is the single most important man-made phenomenon in Iceland? What has this small nation preserved, created or built that matters to the world? We know that that its nature has long served as an inspiration and attraction, but what is Iceland's most important man-made phenomenon? Do we have a building, an object or an idea which can lay claim to being the Icelandic Mona Lisa?

We might as well start looking around. Our architecture hasn't had a direct influence on cultural history, although the Icelandic turf cottage could well serve as a future inspiration for sustainable architecture. Hallgrímskirkja Church, The Pearl, The Reykjavík Swimming Hall – these are all fine buildings, but hardly in the league of Gaudí or Alvar Aalto. And while walking through the National Museum of Iceland, one doesn't find much with a bearing on world history, either; here I must apologize for my old-fashioned presentation, since modern historical studies deal more with putting things into a wider perspective than with this sort of search for the lost ark. Looking at the world's towering cathedrals, precious royal jewels and even the Norwegian viking ships, we can't exactly boast of having been a central influence on world history. However, we should also keep in mind that the West isn't the whole world – for example, there is an exhibition in China which speaks of “the European Civil War of 1939-45”.

Historians consider the historical impact of events. Knowing that they happened isn't enough – in order to be worth anything, they must also have had direct consequences. By these criteria, the Norse discovery of North America isn't exactly an historic event, because it was forgotten. The real history of America happened later, via other routes.

Halldór Laxness is our Nobel laureate, and quite a few of the world's major writers have read one or two books by him, but important as he is to us he is not an icon in the way that Dostoyevsky, Bulgakov or Kafka are. Also, his international impact is limited to the latter half of the 20thcentury. The first Icelander to directly impact world culture during her lifetime is probably Björk. Not only does she assimilate foreign influences and funnel them to Iceland – usually enough to be considered a pioneer in Icelandic art – she also works in the other direction: globally influencing the ways in which people create, which again influences others back home. However, Björk's impact is limited to the years after 1990, and we still have no idea what her long-term legacy will be. So, we may ask: has any work of art, any man-made phenomenon, had an impact comparable to – or even greater than – Björk, Laxness, perhaps even the Beatles or any given Nobel Laureate?

Looking at the Icelandic sagas, we find that they are largely hampered in the same way as the Norse discovery of North America: These were, and are, unique and mature works of literature, but their influence didn't proliferate during their own time. They have thrived well on the margins of world literature, but much as we would like them to, they haven't become international icons in the same way as have, say, the works of Shakespeare. Important as The Saga of Burnt Njal is to Icelanders, one need only compare the significance of a phrase like “Fair are the hills” – a line from the saga that, to Icelanders, is goosebump-inducing – to literary staples such as “To be or not to be,” or “One morning, as Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed into a horrible vermin.”

The Norse Kings' Sagas, written by Icelanders, influenced the history, identity and even development of Scandinavia – contrary to all our traditional ideas of independence, perhaps we actually stabilized and consolidated the Scandinavian monarchy. However, these effects were confined to the Nordic countries, making works such as the Heimskringlaof Snorri Sturluson an interesting example of historic influence on a local scale.

Come to think of it – shouldwriters strive to influence the entire world? Isn't it enough to lend life and meaning your own hometown through untranslatable works? For a millenium, that is precisely what Icelandic poets did. For a thousand years, the artistic efforts of Icelanders were almost entirely limited to poetry – bound by strict rules of rhyme and alliteration, largely impossible to translate and unintelligible to those who don't speak Icelandic.

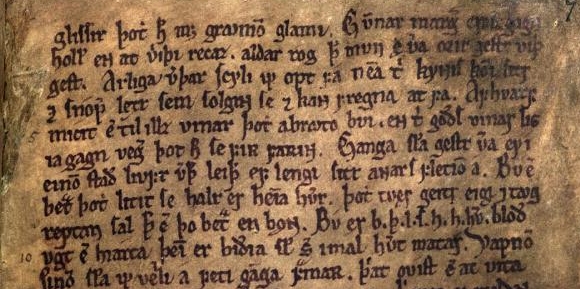

But if it isn't Björk, Hallgrímskirkja Church, Halldór Laxness, The Saga of Njalor the little Thor's hammer in the National Museum – then what is it? Once we have made our way past local heroes, national poets and phenomena directly related to Iceland, we find ourselves in front of a small, modest-looking manuscript made of calfskin. From the tag on its shelf, we read that its designation is GKS 4to, and that it goes by the name of Codex Regius– the Book of Kings. It can be argued that not only is this the most important of all Icelandic manuscripts, but also the most important man-made phenomenon stored in Iceland, and even in all of Northern Europe.

This observation is not based on national hubris or vacuous bragging, but a simple measurement of the density and static energy of art, and measurements of its direct impact on the creation of other people's art. The Codex Regius doesn't specifically refer to Iceland any more than it does to other countries, but – owing to some coincidence – it has been preserved in Icelandic, and is the sole source of much of the texts it contains.

On its journey through the ages, mankind has left behind a number of world views or cosmologies – ideas on the creation of the world, the forces that rule it, the gods who control the destiny of men, the power inherent in words, and, more often than not, an idea of how it is all going to end or begin anew. These world views are intact or complete to various degrees: we have the Jewish world view, the Egyptian, Hindu, Buddhist, Greek, Roman, Aztec and many more. Many tribes have preserved fragments and tatters – perhaps just one sentence, statue or bas-relief. Nordic mythology is one of these ideas. All cosmologies all have some sort of a symbolic center – be it a Buddha sculpture, the Pyramids, an Acropolis, Jerusalem or Rome – but Nordic mythology has no such center which can actually be “seen”, no central museum of international calibre which mediates its cosmology in a modern and interesting way.

The Codex Regius preserves Nordic mythology. Had it not survived, we might not know that the one-eyed man is called Odin, that the one with the hammer is Thor, that the name of the eight-legged horse is Sleipnir or that the dragon is the Midgard Serpent or that it is a sign of wisdom to hold one's tongue, or that money makes fools of men.

The Codex Regius preserves the wisdom of the Völva, and it contains epic poetry which inspired creative minds such as Tolkien, as well as countless painters, sculptors, poets and authors of children's books. The plot of the Codex Regius forms the basis of Wagner's Ring of the Nibelungs. Its philosophy provided authors such as Borges with inspiration for multitudinous stories, poems and philosophical treatises. The Poetic Eddas, found in the book, contain a plethora of archetypes: the trickster Loki, Thor, Odin and the love goddess Freyja. In the Eddas, we find accounts of cruel fate, strong women and mysterious creatures. Their pages harbor the Worm of Midgard, the Fenris Wolf and the avaricious dragon Fafnir. They are full of ancient and exciting things which set the imagination of children and adults alike humming.

Keep in mind that measurements of an artwork's density and static force aren't based on subjective evaluation, but real quantification. A work of art such as the Mona Lisa is world-famous, but, in a way, it has reached its final destination as art; one might even say that it is dead. It has many parodies and imitations, and is probably still inspiring to some, but its direct effect on present day creations, its status as a wellspring of new art, is questionable. However, mythological and fantastic tales, such as the ones preserved in the Eddas, are a constant source of inspiration – a deep-reaching and prime source of ideas, from which artists can continually replenish their creativity. The Norse dwarf Gandalf lends his name to Tolkien's gray-haired sorcerer, the raw material of the Eddas recently appeared as a gigantic Hollywood film on the Marvel Comics version of Thor, the fate of the god Baldur becomes a modern dance work, a painting, a poem, a figure of speech and even a video game. The names from the Eddas are applied to distant planets, brands of chocolate and an oil rig in the North Sea. They have kept both good and bad company. If Icelanders want to create a center for Norse mythology, they just need to erect a framework for the Eddas, capable of mediating their content and impressions. This kind of place could become the most popular tourist location in Iceland, attracting a different crowd than the country's nature presently does.

As a child, you decide where you want to go in your lifetime – sometime, I am going to see the Great Wall of China, the Pyramids and the Pantheon – and Icelanders shouldn't look at this as an opportunity for mere money-making or attracting tourists, but as a nation's self-evident duty in a globalized world. To educate and mediate, to tell stories which encourage understanding and inspiration – that is a role both ennobling and pleasurable. It is a privilege to possess such a perpetual wellspring of art, such a large piece of the world-views left behind by humanity. This world need only be opened – effortlessly and naturally – and new art will spring into existence, as if by itself.

Translation: Steingrímur Teague.

Photo of Andri Snær Magnason: Kristinn Ingvarsson

Photo of Codex Regius: The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic studies