The South Window

“I am becoming more and more interested in what distinguishes the individual, the life that flutters within him, from the world at large; what influence the world in its totality has on our psyche, or whether we are just largely a bundle of nature and nurture, which takes its own course regardless of what happens outside this ‘outer canister', as Þórbergur Þórðarson put it,” says writer Gyrðir Elíasson.

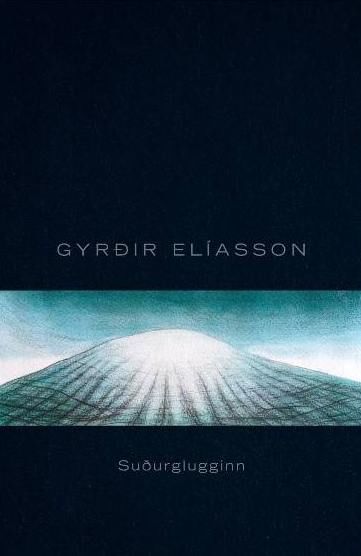

“I am becoming more and more interested in what distinguishes the individual, the life that flutters within him, from the world at large; what influence the world in its totality has on our psyche, or whether we are just largely a bundle of nature and nurture, which takes its own course regardless of what happens outside this ‘outer canister', as Þórbergur Þórðarson put it,” says writer Gyrðir Elíasson. He has just completed a new novel, Suðurglugginn (The South Window), which has been nominated for the Icelandic Literary Prize.

“I am becoming more and more interested in what distinguishes the individual, the life that flutters within him, from the world at large; what influence the world in its totality has on our psyche, or whether we are just largely a bundle of nature and nurture, which takes its own course regardless of what happens outside this ‘outer canister', as Þórbergur Þórðarson put it,” says writer Gyrðir Elíasson. He has just completed a new novel, Suðurglugginn (The South Window), which has been nominated for the Icelandic Literary Prize.

The book is about an author who is staying at a summer-house near a small village; he is writing a novel. The solitude suits him well as he works, but, despite the peace of his surroundings, his writing is not going well, and the typewriter—which in this computer age he insists on using—gathers dust. During his stay in the summer-house the author hardly communicates with other people at all. He writes letters—which he doesn't send—and he receives letters—which he burns unopened. Beneath everything there seems to be a ruined love affair; it is clear the author is disillusioned with life.

Gyrðir says that in this book he inhabits what is psychology's favourite environment. “I believe that fiction can bring out a variety of things about this mysterious ‘inner being', things that academic fields of study perhaps don't capture. I also think that fiction of this kind is just as valuable as the so-called ‘social fiction' that is perhaps more fashionable in the present day. Variety is the spice of life, as the saying goes.”

“A writer's life is always miserable”

“I had been wanting for some time to write an account that in some way describes the reality of a writer's lot,” Gyrðir replies when asked about the origins of the work. “‘A writer's life is always miserable,' Tolstoy apparently said. The protagonist in Suðurglugginn may perhaps not be a typical writer, I can't be sure about that, but that is how he appears to me and I just tried to do him justice to the best of my abilities. But the reader must bear in mind that this is not a novel in the traditional meaning of that word.”

“I had been wanting for some time to write an account that in some way describes the reality of a writer's lot,” Gyrðir replies when asked about the origins of the work. “‘A writer's life is always miserable,' Tolstoy apparently said. The protagonist in Suðurglugginn may perhaps not be a typical writer, I can't be sure about that, but that is how he appears to me and I just tried to do him justice to the best of my abilities. But the reader must bear in mind that this is not a novel in the traditional meaning of that word.”

In what way?

“Halldór Laxness talked about the essai-roman, maybe you could call this book an ‘essay-novella', I don't know. Perhaps definitions are not that important and, actually, the definition of the word ‘novel' has expanded considerably with the advent of modernism. As this is a book of but 25,000 words I suppose it would be considered a novella.”

This year you have published two books, a volume of poems Hér vex enginn sítrónuviður (No Lemon-trees Grow Here) and now, Suðurglugginn. You have actually managed to find time and space to write despite receiving the Nordic Literary Prize?

“I understand that many who have been awarded this prize—or, perhaps rather ‘been hit by it'—have hardly been able to write a thing for a couple of years afterwards, on account of all kinds of distractions and disturbances of that mental wavelength most people need to sustain in order to be able to write. I decided early on that I was going to resist such disruption, and as time went on I began to decline invitations to festivals and suchlike, in order to find time for myself. I have never really enjoyed literary festivals that much anyway, so this was not a difficult decision. After all, a desk is more important for a writer than a high table at a festival, with all the trappings of celebrity that brings.”

One can detect similar themes in Suðurglugginn as in your previous novel Sandárbókin. Is Suðurglugginn in some ways a companion piece?

“Many who have read both books seem to look at them that way. As is often the case with me, I tend to see such patterns in hindsight, and there are, of course, some points of contact in that both deal with the process of creation. But in my opinion there are also many things that are very different, and I don't think that it's simply to do with the format, but rather that the later book took on a different format precisely because of the difference in the content. It would take some time to explain that properly. But I don't mind at all if people want to link these books; the trains of thought are certainly there.”

Gyrðir says that the book has parallels with Ólafur Jóhann Sigurðsson's short story, Hvolpur (Puppy), which he read in his youth. “It is about a man who tries to write, with limited success, just like my protagonist; but other than that the stories are actually completely different. But an artist is forever haunted by this question about solitude and society, and it is a question that will never be answered once and for all.”

But are you not in danger of starving your inner life if you abstain from interaction with other people?

“On the contrary, in some respects you starve your inner life if you abstain from solitude, if I can put it like that; the mind also needs tranquillity independent of others if you want to get something down on paper, for example. But then there's the other point of view, that most people have a necessity to communicate with others. Those who completely cut themselves from their fellows have, generally, experienced a great and deep disappointment in life. This seemed an interesting approach to me and I hope I have to some extent managed to get this ‘tension' across.”

Reality can withstand journeys into other spheres

Dreams are a prominent feature of the book, and Gyrðir says that to some extent they reflect the protagonist's mental isolation, that “he has so far disappeared into himself that he lives as much in the dreams of night as in the everyday; it is something I believe most refrain from acknowledging, as dreams have been so thoroughly dismissed in our technological society that people hardly dare admit to having dreams any more, never mind giving any meaning to them, whether it be psychological or any other. I, on the other hand, stick firmly by what I have said before, that dreams are a fact; they are part of sleep which, after all, comprises as much as a third of our lifetimes, so that it might be sensible to re-invest them with some of that meaning they carried for people in the past.”

Were dreams much talked about when you were growing up?

“Yes, I was brought up amongst people who discussed their dreams seriously, trying to work out their meaning—they didn't say, ‘Huh, it was only a dream.' I don't believe that people need to fear losing sight of reality by paying greater attention to their dreams. Reality is not about to go away, it can withstand small journeys into different spheres.”

The ‘black dog' barks quite a bit in the book. While there is certainly gloom in Suðurglugginn the book is undeniably funny in parts.

“It is true that the book balances heavier notes with those reactions to our existence we call humour, but which are sometimes basically a kind of defence mechanism to suppress as well as deal with that which is underlying. There are, of course, many types of humour, prompted by a variety of reasons and states of mind; and each of its variants has differences of degree. Furthermore, humour is a very individual concept—what one finds funny means nothing to the next person. I don't know if my type of humour has changed much over the years, I leave it to others to judge that.”

In our last interview you said you were aware that many people don't find anything amusing in your books, just “gloomy and depressing prose.”

“I have almost come to accept that some people don't see anything at all to smile about in my writing, whereas before I felt a bit sad about that. On the other hand, humour in writing is to a certain extent a separate issue, important in many ways but sometimes difficult to handle, and there are many other things that carry weight in writing. I often feel nowadays that the concept of humour has been considerably and disagreeably narrowed down into some kind of ‘haha' standard which is actually nothing but blatant vulgarism; you could say that it shows a certain lack of humour not to recognise any other varieties of wit.”

The protagonist in Suðurglugginn has harsh words to say about our present times. His main link to the outside world is the radio, which brings news of wars, environmental disasters, corruption, and seemingly limitless greed. The book has been described as a ‘quiet social polemic', would you regard that as a valid comment?

“You could say there is some truth in that, although I try to avoid sounding like a preacher. But it seems to have ever been thus, that writers have depicted their own times as being in decline; many of the poets of Ancient Rome, for instance, were convinced they lived in degenerate times. But then the question arises, the one that perhaps touches somewhat on the subject of the book: is ‘the present' just this instant within us, this time that we are allocated, or is it something tangible that we, who at any one time together inhabit this planet, either consciously or subconsciously invent? This is what most people say when asked, but I take the view that many people, if they look within themselves, would be inclined to think that the world simply ends with their death. Or as that king once said, “I am the state.” How important to us, really, are those sufferings that the media bring to us from this collective world?”

Is our present time a nag?

“If the news is a true reflection of the world, then it becomes difficult to answer your question any other way than in the affirmative!”