Gyrðir Elíasson

The works of Gyrðir Elíasson, one of Iceland's most renowned authors, reflect the dictum that “real humor needs a tragic sinker.”

The works of Gyrðir Elíasson, one of Iceland's most renowned authors, reflect the dictum that “real humor needs a tragic sinker.”

“Modern writers mustn't entirely forget the individual's inner life, which is still important despite all the external phenomena clamoring for attention,” says the author Gyrðir Elíasson in an interview with Sagenhaftes Island.

His terse prose, precariously balanced between the logical and the fantastic, has won the admiration of readers and critics alike ever since his debut book of poetry was published twenty-eight years ago.

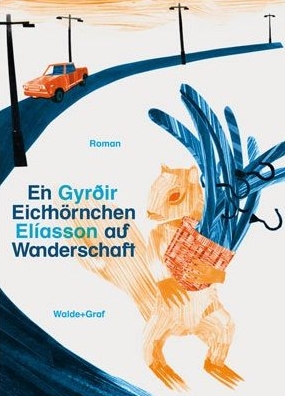

While Gyrðir's works have been translated into many languages throughout the years, he will be especially prominent in the German-speaking world in 2011, with three works appearing in translation in the next few months. The Swiss publishing house Walde + Graf will publish two of his novels, his debut novel Gangandi íkorni (The Wandering Squirrel) in February, and Sandárbókin (The Book of Sandá River) will follow a few months later. Finally, his latest book of poetry, Nokkur almenn orð um kulnun sólar (A Few General Remarks on the Cooling of the Sun) will appear with the publisher Kleinheinrich this spring.

An environmentalist in two senses of the word

Your correspondent had a conversation with Gyrðir over a cup of coffee at his home in Grafarvogur, a suburb of Reykjavík. The rapport between man and environment has always been a prominent feature of Gyrðir's work, which lead to the first question: How does it feel to be a writer in the suburbs?

“You get used to it,” he replies, laughing. “I grew up outside the city, and I've sometimes struggled to find the connection to writing here, but it happens, little by little. Yes, it's just fine, I think. To be sure, I often run into people who ask me how I can live and write out here. I suppose that to someone living in an older neighborhood this isn't a very poetic place.

Remarkably enough, many writers do live here. Just after I moved in, there was an attempt to form a club for the writers in the neighbourhood. But as is often the case with writers, we weren't very gregarious, so now you can say about the club what the poet Steinn Steinarr said of Baudelaire: “Been dead for a long time, thank god.”

There's such a pronounced atmosphere of loneliness and isolation in your poetry and stories. It's hard to picture anyone writing them in the hustle and bustle of the city. Is the environment important to your writing?

“Yes, it is. Usually, the spark, the original idea, comes from outside the city, from somewhere else. The basic idea for a story or a poem might be born when I'm out in nature or somewhere far away, though the final work takes place in the city. Somehow, it's always been like this for me: the environment has always been important to me . My direct influences come from beyond the urban areas.

I may occasionally write about the city, but in a different way, with a different approach. Then again, though I'm always identified with the countryside in everything written about me, I have nonetheless lived in the city for almost half of my life. That changes you in some ways, of course. I remember a critic who said I was “very dependent on my environment.” He was probably right about that, although critics can be any which way in that respect. I guess you might say I'm an “environmentalist” in two senses of the word.”

Humor with a tragic sinker

Your more recent works are characterized by a dark atmosphere, as seen in the title of your latest poetry book: A Few General Remarks on the Cooling of the Sun. Nevertheless, you won the Bröste Optimism Award in 1998. How did this happen?

“That came as a surprise to me! I had never considered myself a likely candidate for that sort of award. I suppose that the idea behind the optimism prize is that the people who award it are optimistic that the winners will be deserving of the honor, and will keep up the good work. But I can't say I think of myself as an optimist. Not before the award, and not after it. Filing me under that category is dubious at best.

Of course, it's always debatable what “optimism” entails, but it certainly doesn't involve burying your head in the sand as has, in my opinion, sometimes been the case here, especially in the heyday of the “feel-good society.” In any case, it's hardly possible to discuss optimism these days without entering the realm of politics, a topic which Hans Christian Andersen very rightly claimed was “best avoided by writers.”

However, there is also a great deal of humor in your work.

That's always been natural to me, I think. These things run together naturally, as in life – laughter and seriousness. Humor doesn't diminish a work's seriousness. On the contrary, it can elevate it, draw attention to it. It's just as the Faroese author William Heinesen said: “Real humor needs a tragic sinker.” I don't find these to be opposites but elements working together. Many of my favorite authors – Knut Hamsun, Richard Brautigan and others – combine the two in a way that speaks to me. On the other hand, humor is always a matter of definition, and I realize that many people don't find any humor at all in my works, just gloomy and depressing prose. There's nothing to be done about that.

Your first novel, The Wandering Squirrel, is due out in Germany this year, and you are a prolific translator yourself. Has this influenced your own writing?

Your first novel, The Wandering Squirrel, is due out in Germany this year, and you are a prolific translator yourself. Has this influenced your own writing?

“Yes, in many ways it has. To begin with, I've chosen to translate authors who are close to my heart, authors who have perhaps influenced me. Diving head-first into the works of other people affects you, no doubt about that. Your style is influenced indirectly by grappling with another language and another mind. The effects are manifold and complex. It's good training for a writer, and not a waste of time as some authors seem to think.Taking a break from oneself while learning something new can be good, sometimes.

As for The Wandering Squirrel, its publication is a very happy occasion for me; no-one abroad ever expressed interest in that particular work before. The publishing house is from Switzerland – a small outfit. Some people don't think highly of small publishers, but I think they're important, both here and around the world. They publish different kinds of works than the big firms, don't place as much emphasis on popularity and sales. They also often do a very good job, not least when it comes to the appearance and printing of the books, which is still important, whatever people say. This edition of The Wandering Squirrel will be wonderfully illustrated, which is appropriate because the book was partially inspired by children's literature, although it doesn't fall into that category itself.”

"Where was the oomph in that?"

Gyrðir says he has a number of works in the pipelines.

“A book can always simply grab the reins, trip you over. Suddenly, you come across something and get to work on it. The Book of Sandá River is a good example of that. I don't know how to plan books but I always use notebooks. Sometimes many years pass by, but in the end, I often use points from them. A note suddenly fits perfectly with something I'm thinking of many years later. There are hundreds of loosely connected fragments behind The Book of Sandá River, short as it is. But there wasn't much text to spare. Very few chapters were cut out – maybe one or two. “I'm economical about my art,” as the painter Gunnlaugur Scheving used to say. I make use of most things."

You aren't exactly notorious for publishing thick, heavy books.

“No, I did reread Hótelsumar (lit. Hotel Summer) a while ago, and felt it could perhaps have been a bit longer! Someone called me Iceland's Anorexic Author, and maybe that's close to the mark. The novella form usually appeals to me. I often feel that books can be trimmed down, but sometimes that sort of thing goes too far. I can't by any rights call myself a novelist, though I've written a few novellas. I have neither the technique nor the stamina to write big novels, so I'll leave it to more able people.”

Perhaps your novels are closer to poetry, then?

“I think they are. That's how I work on them, and it probably shows, whether that's a good thing or not. I'm not ticked off at those who won't admit that they're novels – it's a normal reaction, because they don't obey the laws normally associated with novels. They fit well enough into the category of the novella, though. I also think they share many characteristics with poetry. My work has its foundation in poetry, in part because that's all I can do, and in part because I'm just more interested in that field.

The short-story writing is a part of this. Maybe I can't even be called a short story writer, either. I've always felt that my work is more closely affiliated with what the English-speaking world calls “sketches,” rather than conventional short stories. I have a lot of respect for short-story writers like Alice Munro, for example, but I don't want to do what you might call “canned” short-stories. Just to avoid any misunderstanding, I'm not comparing myself to a world class name in any way.

First and foremost, though, I think that writers have to write from within themselves, without comparing themselves overly to others. They should ignore the competitive aspect as much as they can, steer their ambition partly inward, so that they're primarily competing with themselves. Art isn't a competitive sport, and it's useless – perhaps even contrary to the nature of art – to try to write other people off the table.

But we Icelandic authors are certainly in a rather strange situation, because of the small population, the country's location and so forth. This makes it hard for us to compare ourselves fairly with authors from other parts in the world. I suspect that we often tend to exaggerate the drawbacks of our situation, and don't pay enough attention to its possible advantages. William Heinesen, who wasn't very concerned about the literary isolation of the Faeroe Isles, pointed out that the central points of the world were a matter of personal choice. Another Faeroese, the polymath Tóroddur Poulsen, once said that he had no desire to write in English or any other language everyone else was writing in, because where was the oomph in that? Tóroddur wasn't being xenophobic, he just a had a unique sense of the value of languages, regardless of how widespread they are.”

What is it about the shorter forms that appeals to you?

“The novella is unlike the novel in many ways. It's not just the length but the approach that's different. It's closer to the poem in that regard. This shorter form, which sometimes conjures up flashes of imagery that stay with you for a long time, has always appealed to me. It could be because I was no less influenced by visual art than writing. I grew up with painting, you might say [Gyrðir's father was the Icelandic artist Elías B. Jónasson] and was going to become an artist, but I found out I didn't have the talent for it. Still, I probably took something from there into the writing, but not consciously. It's something you see in retrospect. My grandfather did carpentry, and sometimes I feel that this also has something to say. At any rate, many people feel that I “carve away” too much!

That's the way it is with everyone: there are many diverse influences. Literature isn't a sealed field, even if people sometimes try to build fences around it. It's always part of the environment it grows from. Even when it seems sealed off and turned in on itself, everything always grows from something. Paradoxical as it sounds, choosing not to write primarily about politics or social affairs can be a social stance in itself. Modern writers mustn't entirely forget the individual's inner life, which is still important despite all the external phenomena clamoring for attention. The inner life musn't be underestimated.”

Interview: Davíð Kjartan Gestsson

English translation: Steingrímur Karl Teague

Photograph: Einar Falur Ingólfsson