"I love all my authors" An interview with the Norwegian translator, Tone Myklebost.

Tone Myklebost was recently awarded Orðstír, an honorary award for translations of Icelandic literature to a foreign language. In an interview with Magnús Guðmundsson Tone says she is first and foremost exceedingly grateful for this honor.

Tone Myklebost has translated Icelandic literature into Norwegian for decades. Among the authors she's translated are such luminaries as Einar Kárason, Einar Már Guðmundsson, Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir, Jón Kalman Stefánsson, Gerður Kristný, Sjón, Gyrðir Elíasson, and even Nobel Prize winner Halldór Laxness. All told, Tone has translated more than 50 books, including every one of the Icelandic recipients of the Nordic Council's Literature Prize for the last 25 years.

Tone Myklebost has translated Icelandic literature into Norwegian for decades. Among the authors she's translated are such luminaries as Einar Kárason, Einar Már Guðmundsson, Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir, Jón Kalman Stefánsson, Gerður Kristný, Sjón, Gyrðir Elíasson, and even Nobel Prize winner Halldór Laxness. All told, Tone has translated more than 50 books, including every one of the Icelandic recipients of the Nordic Council's Literature Prize for the last 25 years.

Invaluable reward

Both Tone and Tina Flecken, who translates from German, were honored with the Orðstir, an award that recognizes translators of Icelandic literature into foreign languages at this year's Reykjavík International Literary Festival. In an interview with Magnús Guðmundsson, Tone says that she is exceedingly grateful for this honor. “It's so rewarding when you touch people, and they enjoy what you're doing and appreciate it. It's an invaluable reward to have reaped.”

Both Tone and Tina Flecken, who translates from German, were honored with the Orðstir, an award that recognizes translators of Icelandic literature into foreign languages at this year's Reykjavík International Literary Festival. In an interview with Magnús Guðmundsson, Tone says that she is exceedingly grateful for this honor. “It's so rewarding when you touch people, and they enjoy what you're doing and appreciate it. It's an invaluable reward to have reaped.”

Ég heiti Tone, ég er ellefu ára — My name is Tone, I am eleven

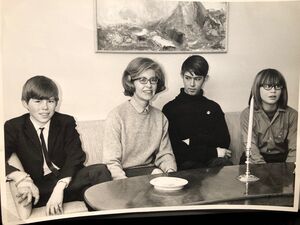

“My childhood home was full of books and newspapers. My mom was a writer, and my dad was a journalist who became the Norwegian ambassador to Iceland when I was 11 years old. Mom and I took the ferry from Kristiansand and Dad met us at the dock in Reykjavík. He wasn't too pleased when he saw that Mom had brought all four of our cats from home,” says Tone with a laugh as she recalls her first introduction to Iceland.

“The very same day we arrived, I put one of the cats on a leash and went out onto Fjólugata, [the street where we lived]. There I stood, a stranger in a strange land, when a boy came riding his bike down the street. He rode back and forth many times, looking at this odd phenomenon—a girl with a cat on a leash—before he finally stopped. Then I said the only thing I knew how to say in Icelandic: “Ég heiti Tone, ég er ellefu ára gömul,” or “My name is Tone, I am eleven years old.” But that was enough that he invited me over to his house and we became friends, and his family became my Icelandic family. The boy, who was the first person I met in Iceland, was Gunnar Rafn Guðmundsson, an actor and a fine man, who unfortunately passed away in 1993. It was because of my friendship with him and his lovely family that I was quick to form the strong ties I have to this country and its people.”

“The very same day we arrived, I put one of the cats on a leash and went out onto Fjólugata, [the street where we lived]. There I stood, a stranger in a strange land, when a boy came riding his bike down the street. He rode back and forth many times, looking at this odd phenomenon—a girl with a cat on a leash—before he finally stopped. Then I said the only thing I knew how to say in Icelandic: “Ég heiti Tone, ég er ellefu ára gömul,” or “My name is Tone, I am eleven years old.” But that was enough that he invited me over to his house and we became friends, and his family became my Icelandic family. The boy, who was the first person I met in Iceland, was Gunnar Rafn Guðmundsson, an actor and a fine man, who unfortunately passed away in 1993. It was because of my friendship with him and his lovely family that I was quick to form the strong ties I have to this country and its people.”

A valuable connection

Her mother's strong connection with Iceland was also formative, Tone says. “My mom was a truly unique woman. After we moved here, she enrolled in Icelandic classes at the university, which, at the time, was really unusual for a woman in her position as the wife of an ambassador. Before we knew it, she was fluent in the language and as a result, she was very popular with Icelanders.”

Her mother's strong connection with Iceland was also formative, Tone says. “My mom was a truly unique woman. After we moved here, she enrolled in Icelandic classes at the university, which, at the time, was really unusual for a woman in her position as the wife of an ambassador. Before we knew it, she was fluent in the language and as a result, she was very popular with Icelanders.”

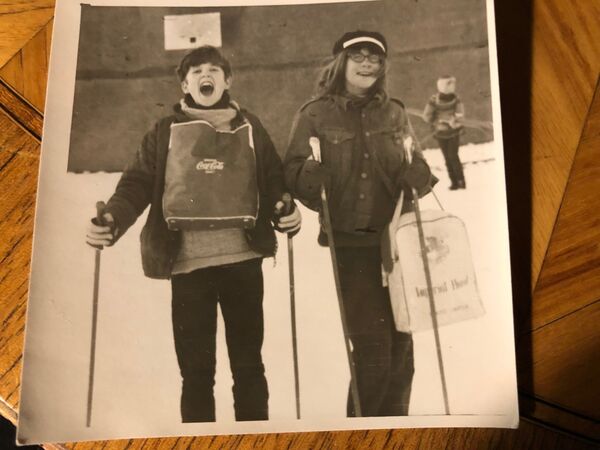

“My brother Terrý, who was 15 years old, was also in Iceland that first year and he and I ran pretty wild. Sometimes, during the short, dark days of winter, we'd go horseback riding alone on the Álftanes peninsula [where Bessastaðir, the presidential residence is located], even though we barely knew how to ride. We rode through the lava fields like lunatics, Terrý in front and me in back. It was unbelievably dangerous, and I break out in a cold sweat when I think about it today. They put Terrý in a remedial class because he couldn't speak Icelandic and he met a lot of kids there who were just as wild as he was. So the next year, he was sent home to a boarding school in Norway.”

Asked for a trip to Iceland

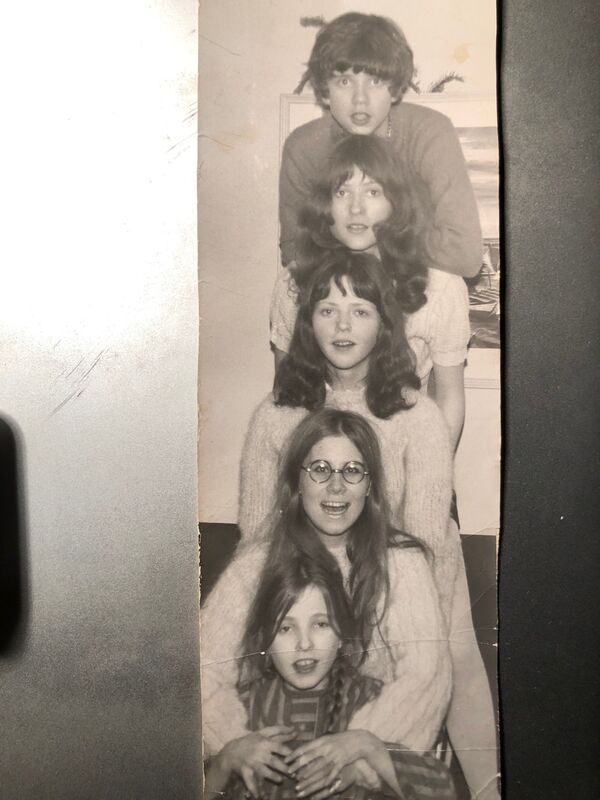

Tone, however, lived in Iceland for two more years. She went to Austurbæjarskóli in downtown Reykjavík and really liked her classmates. Their teacher was the renowned author Stefán Jónsson, which Tone says was wonderful. Ever since then, Iceland has kept pulling her back. “When I was confirmed, I asked for a trip to Iceland as a confirmation gift because I always thought it was more fun being here. Everything was so different and exciting, and that kept me coming back. Then when I was 17, I had a child, which is, of course, incredibly Icelandic, although it's pretty unusual in Norway,” she adds with a smile.

Still has strong ties in Iceland

Tone was twenty when she started a relationship with Ingólfur Margeirsson, a journalist and television personality who served as the Norwegian correspondent for RÚV, the national broadcasting service of Iceland, during the 80s. Tone and Ingólfur had two children together.

“Ingólfur and I first met at the Icelandic embassy in Oslo when I was 14 years old. Dad had just died, and Mom and I were briefly living with [Icelandic diplomat] Hans G. Andersen and his wife, Ásta. Ingólfur came to visit their son Gunnar. Six years later, we got together in Stockholm, but the place we lived together longest was Oslo. We actually had a home in Iceland from 1978-1980, so I know a lot about living in Icelandic society, even though I only lived here for five years total. But I've always had one foot in Iceland, so to speak, and the strong ties that I formed here during my childhood live on. All of this turned out to be really valuable when I started translating Icelandic literature into my mother tongue.”

Three books in five months

Since she basically learned Icelandic ‘on the street,' Tone says, she decided at one point to enroll in a university program to better learn the grammar. “I realized that [all my classmates] were much better at it than I was, and when I came to this scientific conclusion, I decided to let a few weeks suffice and dropped out. But the thing I had over those fine folk was that I could speak Icelandic and anyway, my grammar's improved over the years.”

Tone worked as a journalist at Aftenposten for 13 years, during which time, she often wrote about Iceland. In 1990, she went to a literary festival in Gothenburg where she met authors Halldór Guðmundsson, Örnólfur Thorsson, and Einar Kárason. “The whole thing was a lot of fun and the idea was raised that I should translate Einar's book Djöflaeyjan (English title Devil's Island, trans. David McDuff), which was really popular at the time. I'd never translated anything, but they trusted me, as did the publisher, Ashehoug. And so Djöflaeyjan became my first translation.”

“No one could say I got off to a slow start, because Ashehoug had me translate the whole Island trilogy in five months, which I pulled off. I've never dared to take a good long look at [those translations], but I do remember that I got positive reviews. One even said that [the translations] marked the arrival of a new voice among translators. After that, there was no turning back.”

Bored to death by the end

Since then, Tone says the projects have come rolling in, although she continued to translate on the side while working as a journalist for over a decade. “I didn't translate much at the time, but among [my translations were] Gyrðir [Elíasson] and Einar Már [Guðmundsson]. This changed considerably after my mom died. I was in a really bad place, and it took a lot out of me to be a freelance journalist, always having to hustle for jobs, whereas translations always came to me without my having to do anything. As a result, I decided to dedicate myself to translation and I've always had more than enough to do.”

Asked whether the work of translators earns much respect in Norway, Tone smiles and says, “It's an incredible amount of work to translate. It's poorly paid and there's little prestige. So that isn't why I do what I do. Although the thing about there being little prestige actually changed after Jón Kalman became a hit in Norway. I remember being at a funeral in 2016 when this woman realized that I was Jón Kalman's translator and I could hardly make out what the poor lady was saying. She was totally starstruck,” says Tone, laughing at the memory.

But translating really is hard work, Tone continues. “Going through a 500-page book four or five times will naturally make one a bit unstable. I start grumbling every time, say I'll never do it again, but my children have long said that these are empty declarations because before I know it, I'm back at it again. I think the reason is that I love starting new things. My love of all things new and my curiosity keep me going, but I must admit that more often than not, I'm bored to death by the end.”

Invaluable conversations

“My problem is that I'm indecisive by nature,” adds Tone, pointing out that this is especially unlucky for a translator. “You have to make decisions all day and those decisions are then made final in book form. All those decisions are hard for me, and sometimes, it's hard for me to send off a manuscript because I think I might be able to make something even better. But at a certain point, you've just got to let go of it.”

Tone says she has little contact with the author when she's translating a book, but she does take advantage of her friendship with Imba, or Ingibjörg Guðmundsdóttir, the older sister of Gunnar Rafn, who she met when she was 11. “Every now and then, there are words or even sentences that seem like they could be interpreted in one of two ways, maybe even more. That's when it's great to have a friend like Imba, who will take the time to look it over and discuss it. That's been invaluable for me.”

I lose faith sometimes

Over the course of her career, Tone has translated many different authors and in so doing, she's learned how to capture different styles and nuances. Asked whether her approach to learning Icelandic—that is, informally versus in a formal academic setting—has played a role in this, she says that the most important thing for her is undoubtedly that she knows both Iceland and its people very well. “I came here as a child, came back as a teenager, and also lived here as a mother. I've been here during many different periods of my life and know people from all different social strata, so Iceland isn't really foreign to me. And on top of that, I have my Icelandic family and friends who I keep in very close contact with.”

Known as "that Icelander" in Norway

“It does happen sometimes, however, that these same bonds cause me to lose faith in my translations, to feel like I'm not capturing all the nuances of a language I genuinely love. I think Icelanders have a really fun way of using their language and that's really special to me. Which is why trying to get it across is really close to my heart, but sometimes, it's quite a difficult challenge. What ends up being the most important thing for me is to use Icelandic a lot. Iceland—its people and its language—it's a big part of my identity. There's a reason that in Norway, I'm looked at as ‘that Icelander.'”

“It does happen sometimes, however, that these same bonds cause me to lose faith in my translations, to feel like I'm not capturing all the nuances of a language I genuinely love. I think Icelanders have a really fun way of using their language and that's really special to me. Which is why trying to get it across is really close to my heart, but sometimes, it's quite a difficult challenge. What ends up being the most important thing for me is to use Icelandic a lot. Iceland—its people and its language—it's a big part of my identity. There's a reason that in Norway, I'm looked at as ‘that Icelander.'”

Translation is like a game of dominos

Tone points out that the translation process varies a lot, depending on the authors. “I've translated any number of Icelandic authors over the years and every single one of them has given me so much through their work. As a result, I love all my authors and I want to thank every single one of them.”

“Myself, I am a poetic person and Jón Kalman, for example, writes really poetical books that suit me well, in spite of having these long sentences where you have to be really careful to make sure you've kept all the threads in order. When I've finished translating a 500-page book by Jón, I'm more than happy to sit down to a 200-pager by Auður Ava [Ólafsdóttir], with her clipped and straightforward style, although when you get down to it, that can be even harder to get across in Norwegian.”

“Sometimes I decide late in the process to flip a sentence or something in that vein, but that always has consequences. A change in one place often necessitates a change in another, and so on and so forth, such that translation is often like a game of dominoes where everything must still be standing at the end.”

Magnús Guðmundsson took the interview for The Icelandic Literature Center. Translated by Larissa Kyzer.