“I wanted to open this world to my compatriots.”

“We simply lack the words. We don't have all these words to describe each tussock and every blade of grass. The same goes for certain gestures and actions such as the verbs "rumska" and "smjatta" and other intriguing things that we have no words for.”

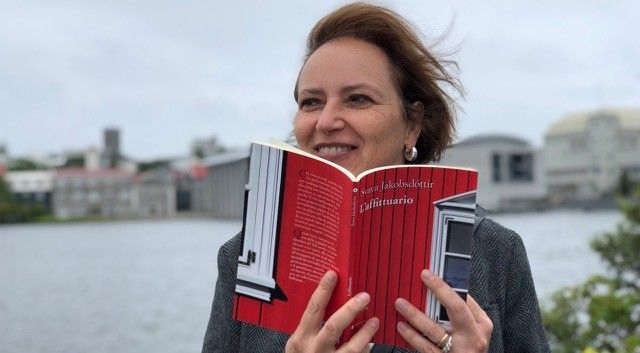

Silvia Cosimini has translated over 70 Icelandic books into Italian, from Sagas to modern novels, and in conversation with Magnús Guðmundsson she talks about how this all started because she was the right person in the right time.

An Enthralling World

“I was just around twenty learning English and German at the university in Florence when I was to take an exam in comparative linguistics in Germanic languages. To prepare for the exam, we read the Saga of Hallfredur, and that opened a whole new and intriguing world to me. A world that I had not even known existed. It was a literary world that immediately enthralled me. I suddenly had prose without an author, and this was completely different to the Medieval literature I had known from the same time. I found it preposterous that many of us had not even been aware of its existence.“

Silvia says that the idea to become a translator had not yet come to her at the time, not at all in fact, as she puts it. “This interest of mine in Icelandic Medieval literature became a theme in my studies and I wrote my final thesis on Old Icelandic. In it I focused on communications between Iceland and Ireland in the Middle Ages, and at the time I was determined to become a specialist in Old Norse.“

No Mercy at Árnastofnun

Silvia decided to do a PhD and received a grant from the University of Florence to go abroad to conduct research and study in the field. “So I went to Iceland, came to Reykjavik and was offered a work station at Árnastofnun [The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies]. That was fantastic. It was in November 1992 and I remember that there was a lot of snow. It was all very alien and in fact Reykjavik was dreadful at that time, very different from the city today. But for me as a researcher of this material it was brilliant to have the opportunity to have a place in Árnastofnun. You can't get much higher in this field than having a place there, at the heart of the study field. All the professors I had referenced in my thesis sat there in the same building and I met them in the hallways. It was a special feeling.”

Kept Quiet the First Year

Silvia says that she quickly realised that she needed to learn modern Icelandic since she had been given this opportunity. “It was also because the people in Árnastofnun were very strict teachers and didn't cut me any slack, which of course paid off in the end. They just spoke Icelandic to me, and I was a bit shy to speak and kept quite quiet the first year. I am extremely grateful for this today but now when I come to Iceland people constantly speak to me in English. I spent four years in Reykjavik and at the end of that period I also graduated from the University of Iceland with a degree in Icelandic for Foreign Students, and this time in Iceland turned out to be the basis of my career.”

It was during this time that translations of Icelandic texts started to become a part of Silvia's life, and her final thesis was a translation of Kormak's Saga into Italian. “It is yet to be published but I am working on that.”

Wanted to Open this World to her Compatriots

“I graduated in 1996 but during my studies I discovered that there is not only Medieval literature that we Italians are unaware of but also modern literature. Italian translations of Icelandic literature were almost non-existent at that time and I wanted to open that world to my compatriots. I felt it was such a shame that we could read so little of Icelandic literature because there was nothing around except a bit of Laxness after he got the Nobel Prize, and then I think there was one novel by Einar Már.

So, I sat down and started to write to Italian publishers, proposing Icelandic works that would be ideal for them to publish. That went on for about couple of years and at the same time the Scandinavian wave was gaining momentum in Italy. It started with works like Peter Høeg's Smilla's Sense of Snow. So I proved to be the right person at the right time.”

Taking on the Italian Image of the Mother

Silvia says that when she started translating Icelandic literature, she had various criteria. “I chose works that I felt were the most exotic but also entertaining and interesting. I started with translating a collection of short stories by Svava Jakobsdóttir because I immediately fell for her as an author. In Italy we had never seen anything like Saga handa börnum. In our society the mother is absolutely untouchable. She is a holy figure in our Catholic community. That's why I thought it was ideal to translate Saga handa börnum where Svava's grotesque and absurdism take on this image and overthrow these ideas.”

When Silvia read 101 Reykjavik by Hallgrímur Helgason she thought it was perfect for the Italian publisher of Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting. “I thought it might be clever to take it there and I was right. I had just started translating when I took on 101 Reykjavik but I still think that I did a good job and it was rewarding that the book was a hit.”

Has Translated around 70 Icelandic Books

Svava's collection of short stories was published in Italian in 1999 and 101 Reykjavik a couple of years later. At the time Silvia was working for a publishing company in Italy. “But I was mostly working from English and German there and the Icelandic material waited at home. I was trying to work on translating Icelandic literature in the evenings and during the weekends, in addition to teaching English in secondary school. But after working like this for a few years I took the big step, I suppose it was in 2005 or 2006, and I quit these day jobs to became a full-time translator.”

Silvia has translated around 70 Icelandic books in all and is apt in different genres of literature. Among Icelandic writers she has translated work by are Hallgrímur Pétursson, Halldór Laxness, Guðbergur Bergsson, Sjón, Arnaldur Indriðason, and Jón Kalman Stefánsson. She says that some books are certainly more difficult than others and mentions that Hallgrímur Pétursson was for instance quite the challenge. “It was the first book I translated and there were two of us. But I work a lot and solely from Icelandic but I'm certainly not the only translator in Italy translating Icelandic literature. Alessandro Storti translates from Icelandic, but also from Swedish and Norwegian so he doesn't manage as much. And then I should mention Stefano Rosatti who lives in Iceland and translates Auður Ava. So it adds up.”

Tries to Influence Publishers

When asked if she has any say in what books she takes on or if it's entirely in the hands of publishers, Silvia says it a little bit of both. “Sometimes publishers buy rights to a book at book fairs without knowing what is in them. That is ridiculous,” Silvia adds and laughs.

“But they also receive grants from The Icelandic Literature Center and that helps to promote Icelandic literature because it helps with the cost of the translation.”

Always Listens to Rás 1

Silvia says she comes to Iceland each year and that helps her a great deal in following current events. “I also always listen to Rás 1 [National Broadcasting Service's channel 1] when I am working at home. There is a lot of coverage on books and Icelandic literature and that keeps me informed about the hottest topics at each time, which in turn means that I sometimes get to participate in selecting works for translation. Still it seems like certain brilliant writers who I am fond of are simply not in favour with Italian publishers. Bragi Ólafsson's books for instance, and now Guðrún Eva's Italian publisher has pulled out and I think that is a shame. I think Guðrún Eva is just fantastic and there is no other author in Iceland today who writes likes her.”

Loves Translating Books of Older Generations

It is evident that Silvia has her favourite writers and they are of various generations and genders. She has however mentioned that she particularly enjoys translating books of older generations. “I want to do more of that, not least because I find that we lack more comprehensive knowledge of 20th century Icelandic literature aside from Laxness. Writers such as Indriði G. Þorsteinsson, Ásta Sigurðardóttir, Guðbergur Bergsson, Jakobína Sigurðardóttir, and others – even Guðrún frá Lundi. I think it would help in understanding what happened in Icelandic society around WWII if there would be more of an effort to translate and research these writers.”

More Joy in Storytelling in Works by Icelandic Authors

With regard to whether Icelandic authors tell stories completely differently than their Italian counterparts, Silvia says that there is a certain difference. “Somehow there is more joy in the storytelling in works by Icelandic authors and there is also more freedom in the composition. Somehow more is allowed. Then there is also a certain difference in the subject matter, as can be seen for instance in how Icelandic writers are always describing the weather and there is also a lot more of landscape descriptions. This is exotic to Italians and in there you often find a struggle between humans and nature, and that is no longer present in Italian literature.”

Lacking Words

Silvia says it can be quite tricky to translate all these weather and nature descriptions into Italian. “We simply lack the words. We don't have all these words to describe each tussock and every blade of grass. The same goes for certain gestures and actions such as the verbs rumska [to stir (from sleep)] and smjatta [to chew noisily] and other intriguing things that we have no words for and so you find that you need to add an adjective to fully explain the gesture.”

Silvia points out that it often takes her by surprise how tricky books can be. “I have for instance just completed the translation of Tvöfalt gler by Halldóra Thoroddsen, and that got trickier as the work progressed. The same goes for Mánasteinn by Sjón because I was so intrigued and surprised by this film scene in Reykjavik during that era. Leitin að svarta víkingnum by Bergsveinn Birgisson was also a highly interesting project because I got to take on the subject I had studied at university. It was tough but I was home nonetheless.”

Valuable Encouragement

Last year Silvia Cosimini was awarded the honorary prize Orðstír for translators of Icelandic literature working into foreign languages. She received the prize along with John Swedenmark from Sweden. When I bring this honour up it is evident how pleased she is with it. “It is a great honour and there are many translators in the world who deserve this. It was a very nice feeling and I have to mention that it demonstrates exactly how aware Icelanders are of the importance of translations. How important translators are for the literature of small nations. It's also evident in the translators' seminar that the Icelandic Literature Center hosts, because there we get a chance to compare notes. That is incredibly valuable.”

When asked how translators are treated in Italy Silvia says that conditions are not ideal. “We have somehow always been seen as some sort of dogs bodies, but attitudes are changing slightly. We have just founded a union in order to try to improve our pay and terms. As things now stand, I sell my translation to a publisher who then own the rights for 20 years. That is much too long as he can do as he pleases with the work during that time. But it's difficult as always, and therefore it is valuable to receive encouragement like the honour that was bestowed upon me in Iceland.”

Silvia says that she is working on Andri Snær Magnason's book Um tímann og vatnið, which she says is a good example of a book that is extremely relevant. “In my opinion it is important that a book like this, which addresses the dangers of global warming, is coming from Iceland. That it comes from a country that has to deal with this directly and that shows us that Icelandic literature really does matter.”